Musk’s Speech is Not Free

Elon Musk promotes himself as an avatar of free speech on X, the platform he runs that used to be Twitter. But I wonder if Mr. Musk and his operation are what James Madison had in mind when he spearheaded the drive that codified free speech in the First Amendment?

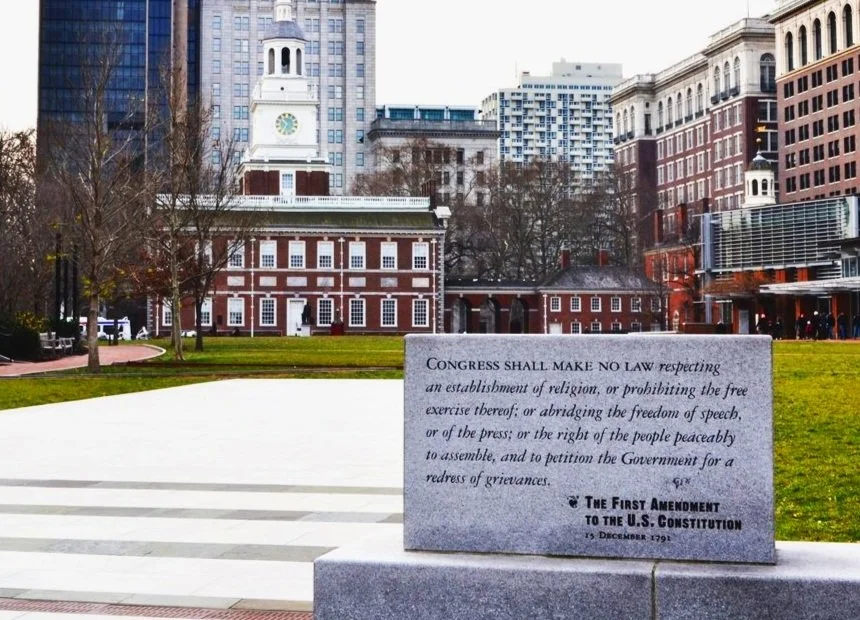

The First Amendment to the Constitution is aptly named for being the most important. I share that sentiment. Its’ wording is a bit out-of-step for a world where most people get their news from X or TikTok or some other social media platform.

Nevertheless, the amendment’s meaning is as vital as when Virginia became the required eleventh state to ratify the nation’s Bill of Rights on December 15, 1791. The vote seared into law the basic rights that distinguish America from any nation across the globe.

The inscription of the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in front of Independence Hall in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

A fierce fight preceded the exact wording of the First Amendment, and Madison played a consequential role that makes a mere billionaire like Mr. Musk look like a pauper. Initially, he fought for a measure that would have covered a broader definition of the average American’s basic rights. Modeled on a version passed by the Virginia ratification convention, it read: “The people shall not be deprived of their right to speak, to write or to publish their sentiments, and the freedom of the press, as one of the great bulwarks of liberty, shall be inviolable.”

Madison’s colleague, Thomas Jefferson, suggested Madison go even further with a declaration that “the federal government will never restrain the presses from printing anything they please.”

Congress, then as now, included competitive partisan geographical and political interests that weighed in on the language. The First Amendment they finally approved is the one we have. Besides freedom of speech and the press, it added several rights that the Founding Fathers had just fought a revolutionary war to win. It reads:

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

Many historians and commentators have wondered whether Founding Fathers such as Madison would have codified such sweeping rights had they envisioned a world with Elon Musk, who routinely spews misinformation and demagoguery to huge audiences, or former president Donald Trump, who capitalizes on compliant media to spread lies and innuendo.

In Madison’s day, the media was different, but not as much as one might imagine. Highly partisan and politically charged, newspapers, then the dominant medium, aligned their editorial policies with political parties or partisan factions, serving as mouthpieces for narcissistic political views. In effect, the politicians covered themselves in letters to constituents. Indeed, at the time, the partisan nature was seen as an essential part of the political discourse rather than a drawback, similar to the barrage of political ads that saturate current airwaves during campaign seasons.

Madison believed that newspapers should be distributed through the mail free of charge, viewing any postage fee as a burdensome “tax on newspapers." Modern media retains a less generous government subsidy. Local laws mandate that government agencies publish legal notices in newspapers, giving them ad revenues that are a lifeline for small publications across the nation.

In reality, though, the political elite in Madison’s times formed the major newspaper audience because the publications were relatively expensive and, for the most part, required subscriptions few could afford. They were often passed along from impoverished reader to reader or read aloud in parks and public spaces for the illiterate. The news of Madison’s day could also be as ugly, sensational, and misleading as anything Mr. Musk allows on X.

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of journalism --- and it is no small irony that the former condition led to the latter, that the golden age of America’s founding was also the gutter age of American reporting,” Eric Burns wrote in “Infamous Scribblers, the Founding Fathers and the Rowdy Beginnings of American Journalism.”

“The Declaration of Independence was literature, but the New England Courant talked trash,” wrote Burns, a journalist and author in his entertaining and authoritative book on journalism in America’s earliest days. “The Constitution of the United States was philosophy, the Boston Gazette slung mud.” Newspapers such as the Gazette of the United States and the National Gazette were conceived of as weapons, Burns wrote, not chronicles of daily events, and the Founding Fathers used the media for everything from thoughtful essays to scandalous leaks that were every bit as bad as Mr. Musk’s musings on X.

What is different, though, and what makes Madison a more substantial person than Mr. Musk, is the path the billionaire took when he turned Twitter into X.

Madison and most of the Founding Fathers acted out of principle. An autocratic king who ordered how they could worship, gather, speak, or write lingered in their memories when they drafted the First Amendment. They would tolerate the abuses later documented by Burns to create a democracy with the rights citizens needed for access to information. They trusted the electorate to sift fact from fiction because informed citizens would make the best decisions, although Madison’s liberal views didn’t extend to his contradictory conduct regarding the slaves that he owned. Like most of the Founding Fathers, slavery remains a stain on their reputations. Nonetheless, Madison remains history’s champion of the amendment that gives every citizen the right to criticize him because he never freed his slaves.

photo of bust of James Madison in Independence Hall taken by the author

Mr. Musk’s motives are far more complex. He is a member of an unofficial club that, in act and deed, disparages the principles that characterize Madison’s passionate belief in the First Amendment. Mr. Musk is a creature of an Internet medium that shapes his conduct, not an avatar of free speech. Under his hand, X almost demands sensationalized posts to build the traffic that has dramatically declined since he took over. Like most of the mainstream media, he capitalizes on the ability of his new best friend, Donald Trump, to capture attention and get traffic on his money-losing site. He allows misinformation like the hoax that Haitian immigrants were eating pet cats and dogs in Ohio to appear on X. He makes crude references to Taylor Swift’s endorsement of Vice President Kamala Harris and airs softball interviews with Trump, his choice for President. He wants traffic and the money it can bring to bail him out of a bad investment. But it hasn’t worked. Traffic is down twenty percent since he took over.

Mr. Musk has every right to air whatever he likes on X. We do, after all, live in the only country in the world with a constitution that prohibits the government from imposing limits on what we read in the press or say publicly. I believe strongly in free speech, and I’d rather tolerate Mr. Musk and his dopey jokes on X than have the government decide what citizens can say, hear, or read.

But freedom of speech places on the shoulders of its champions the burden of a respect for accuracy, a sense of decency, context, and an aversion to mere rumor. Despite his faults, James Madison demanded that the Bill of Rights codify the freedom to speak one’s mind because he knew what happens when kings think otherwise. Mr. Musk is using X for his personal, selfish ends. He lacks credibility. That’s why he is losing so much money.

Were Madison and his friend Jefferson, also a slave owner, alive, I’ll venture to say they would tolerate Mr. Musk and his antics on X because, eventually, he will be judged on the accuracy, context, credibility, and integrity of the words he uses, just as history would later put the two Founding Fathers in proper historical context.

—James O’Shea

James O’Shea is a longtime Chicago author and journalist who now lives in North Carolina. He is the author of several books and is the former editor of the Los Angeles Times and managing editor of the Chicago Tribune. Follow Jim’s Five W’s Substack here.