What Puts the Ire in Ireland?

Words and will animate Máirtín Ó Muilleoir

In a world where media organizations of all sizes struggle with the prospect of a journalistic judgment day, Máirtín Ó Muilleoir shows that one man who won’t give up can make a difference.

In contrast to the stories of young entrepreneurs who create digital magic with sites like TikTok, Ó Muilleoir embodies the passion and commitment needed in the existential fight for the survival of local public service journalism. There’s no guarantee that he or anyone else will win the fight. In fact, the prospects for the future are rather grim. Nevertheless, the witty and wise-cracking Ó Muilleoir refuses to cave in.

photo of Máirtín Ó Muilleoir, former minister of finance in the Northern Ireland executive courtesy Institute for Government

“As long as there’s Black Mountain above West Belfast, there’ll be an Andersontown News, Ó Muilleoir vowed in a story he wrote just months ago commemorating the 50th anniversary of one of the local newspapers he runs.

As the journalistic entrepreneur and political figure in Northern Ireland, Ó Muilleoir unsuccessfully put his papers up for sale in 2019. He nonetheless continues his drive to keep afloat the gutsy local newspapers of the Belfast Media Group, where he is managing director.

His goal is simple: to keep alive the Andersontown News and its sister publications that cover north and south Belfast despite the financial headwinds threatening the future of local news publishers everywhere.

Ó Muilleoir’s Belfast papers crackle with lively local stories ranging from an obituary for Steek Mcgaw’s beloved dog Shep to the political brawls and tragedies memorialized by murals on the sides of Belfast buildings — tableaus of the heroes and villains spawned by the Northern Irish city’s tragic history.

“[The founders] vision was of a newspaper that would give voice to the truths ignored by the main media,” Ó Muilleoir said of the Andersontown News, — “truths about murder, injustice, collusion and repression which, indeed, would only be acknowledged two generations later.

Over the years, he’s used his wit, candor and his own financial resources to overcome opposition that would thwart the will of publishers and readers alike. The Belfast City Council once imposed a ban on advertising in the Andersontown News that was eventually overturned by an ombudsman, Ó Muilleoir said, and the former Northern Ireland police force tried to block social clubs from advertising in his pages, a move he characterized “as a flat-footed effort at censorship.

“It resulted in a cat-and-mouse battle of wits,” he said, “which resulted in a swift victory since our opponent was unarmed.”

In publishing and politics, Ó Muilleoir displays a strong commitment to peaceful solutions to the tensions that, although diminished, remain between the Protestant and Catholic communities in Belfast. His papers display his resolve with stories and editorials that show his willingness to challenge power with coverage of controversial issues that risk financial ruin.

In 2005, he started publishing the Daily Ireland newspaper, to air the controversial views of Sinn Fein — a minor political party at the time with close ties to the Irish Republican Army — a source of violence and terror. Opposition from all wings of the Irish political establishment greeted Ó Muilleoir’s new paper. The British government refused to recognize it. One government minister called it a “Nazi newspaper.”

“It was a pro-Irish Republican newspaper at a time when the government was on an offensive against Irish Republicans,” he told me in a recent interview. The paper gained a significant following with its journalistic campaigns for Irish nationalism, reunification and the use of the Irish language — all positions that earned the paper the ire of Protestant unionists.

“So, if you’re an advertiser and you’re told by the Minister of Justice that this is equivalent to a Nazi newspaper, you’d be afraid to advertise in that newspaper.” But Ó Muilleoir fought back editorially with campaigns for crucial steps needed for peace, such as the decommissioning of weapons by paramilitary groups such as the IRA.

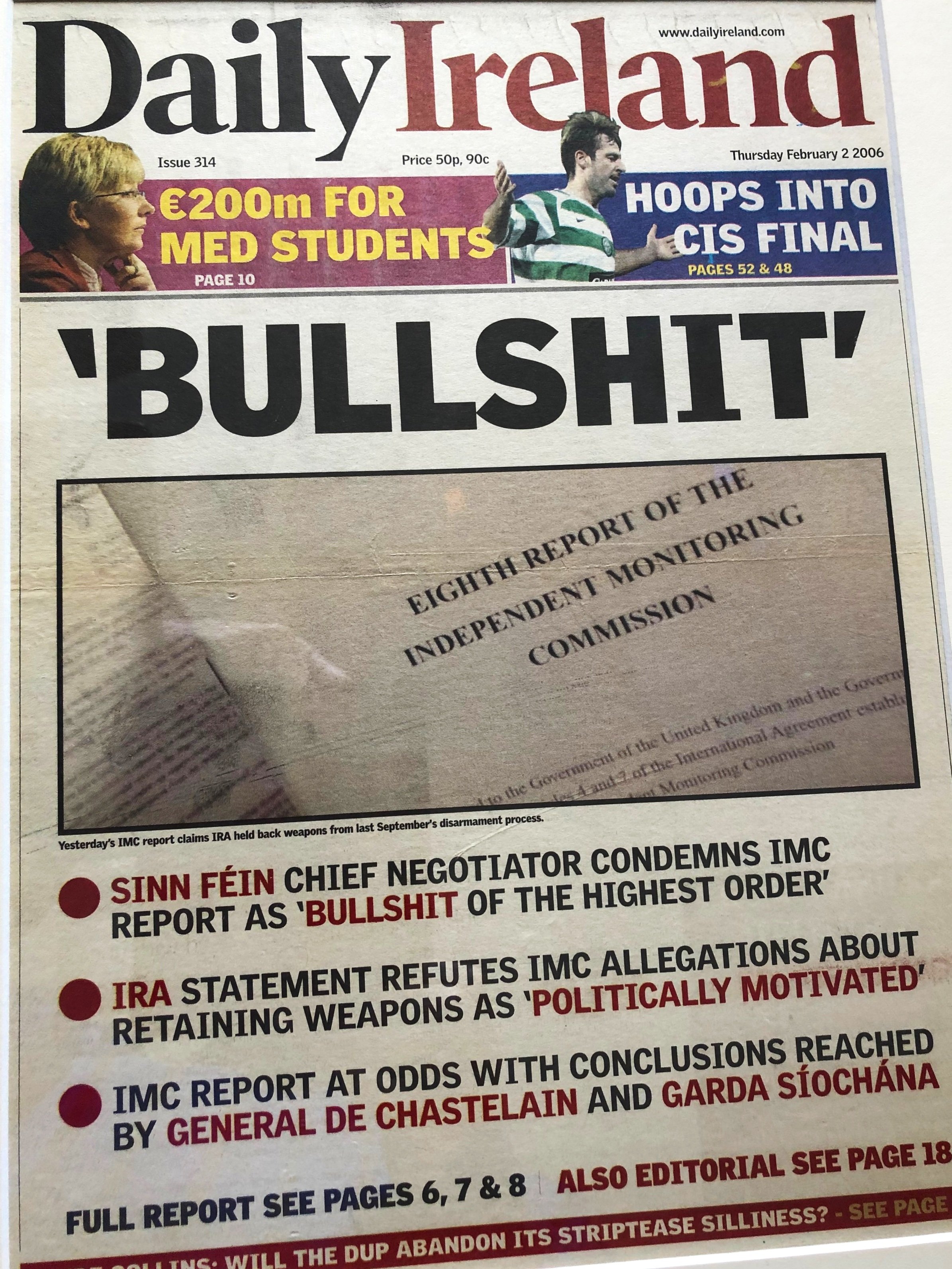

front page of the Daily Ireland, February 2, 2006

Indeed, when a government sponsored monitoring commission issued a report that said the IRA had not fully abandoned its guns, the Daily Ireland published an edition with a boldface headline stretched across the front page: “BULLSHIT” which echoed Martin McGuinness, Sinn Fein’s, chief negotiator, who said the panel’s report was “bullshit of the highest order.”

“It was all very difficult,” Ó Muilleoir told me, “But [the paper] played a vital role at the time pushing forward the peace process. Sinn Fein worked with the IRA to achieve decommissioning” despite what the panels’ report said. “At that time,” he told me, “Sinn Fein I think had one seat in the Southern Irish parliament. Today it is the biggest party on the island by votes in both the Southern Irish parliament and Northern Ireland.”

Sinn Fein’s political success didn’t extend to the paper that championed its cause, though. Ó Muilleoir estimates the paper lost about $3 millon largely due to government sponsored advertising bans and the costs associated with printing and distributing print newspapers. “It was very difficult, and we had a run of it for about a year and a half. We enjoyed it enormously.” He closed it in October 2006, just 21 months after it launched.

Ó Muilleoir now focuses on a different threat, in many ways one more ominous than advertising bans and the fractious politics of Northern Ireland. Advertisers, a crucial source of revenue, are deserting print publications like the Andersontown News in droves.

“I sit everyday beside the ad team and hear them ringing up people who sell carpet, the people who sell furniture, the people who sell TVs, the people who put antennas on your roof and I hear these people saying ‘I’m on Google. I’m on Facebook and I’m getting results from Facebook’. So, you know, we are swimming against the tide.”

Like other publishers across the globe, Ó Muilleoir has imposed cost cuts, staff reductions and economies to keep his costs below declining revenues, all of which adds up to fewer reporters to cover important local stories.

“We’ve gone online,” he told me. “We have a very strong website. We have `200,000 unique visitors a month. So, I think it’s a strong website.” But the Googles of the world have driven down ad rates so much that the site loses money. He says he’s considered erecting a paywall to charge for access to the site, but few readers typically pay.

“You know we’d get three percent of a readers willing to pay for it, five percent? So, you’re losing 95 percent of your public,” Ó Muilleoir told me. “How can you be involved in public service journalism if you only serve five percent of your readers who are internet savvy and wealthy enough to pay for it?”

Ó Muilleoir remains committed to public service and maintains his political ties to Sinn Fein. He also served a year as the Lord Mayor of Belfast. But he questions how local news organizations can serve the public and survive without something that is hard to come by both in Northern Ireland the America — aid from governments and philanthropic organizations.

“This is a new concept in the north of Ireland because philanthropic funds previously went to helping feed kindergarten kids. When we go to them and say a strong newspaper provides the foundation for healthy, cohesive strong community they really don’t know what we are talking about. So, we have to start a process of education.” Governments are typically hostile to helping the press that covers them.

Ó Muilleoir has been scouring America and Ireland seeking resources. Unlike Northern Ireland, he says governments in Australia, Scotland and the south of Ireland are beginning to recognize the extent of the problem and to consider financial help.

“We have to explain that a community with local public service media holding government to account and giving the community a voice is a stronger community than one that doesn’t.”

Although he is not optimistic about the status quo in local journalism, Ó Muilleoir gave his organization a shot in the arm when acquired the Irish Echo weekly newspaper in America. “I’m very pleased with it. It’s a small profitable newspaper that we send out by post to every state in the union. It’s online and for sale in shops in New York.” However, the secret of success is six major events a year where people pay to attend events like the recent Irish Arts Awards in Buffalo.

And he still has ambitions beyond the “Donate” button he’s placed on his papers like the Andersontown News. “We have a strong Syrian community in Belfast which fled the war and are refugees. They remain isolated from the broader community in many ways. So, I’d like to say to a government body that is dealing with issues of inclusion and integration that we’d like [to get some funding] for a columnist — one writing in Arabic.”

—James O’Shea

James O’Shea is a longtime Chicago author and journalist who now lives in North Carolina. He is the author of several books and is the former editor of the Los Angeles Times and managing editor of the Chicago Tribune. Follow Jim’s Five W’s Substack here.